Last week, a massive plume of solar plasma collided with Earth’s atmosphere, creating stunning northern lights visible across the U.S., even reaching as far south as Southern California and Mexico.

This incredible phenomenon was the result of a severe G4 geomagnetic storm caused by the solar ejection impacting our magnetic field on October 10. The spectacle was so spectacular that it was even captured from space.

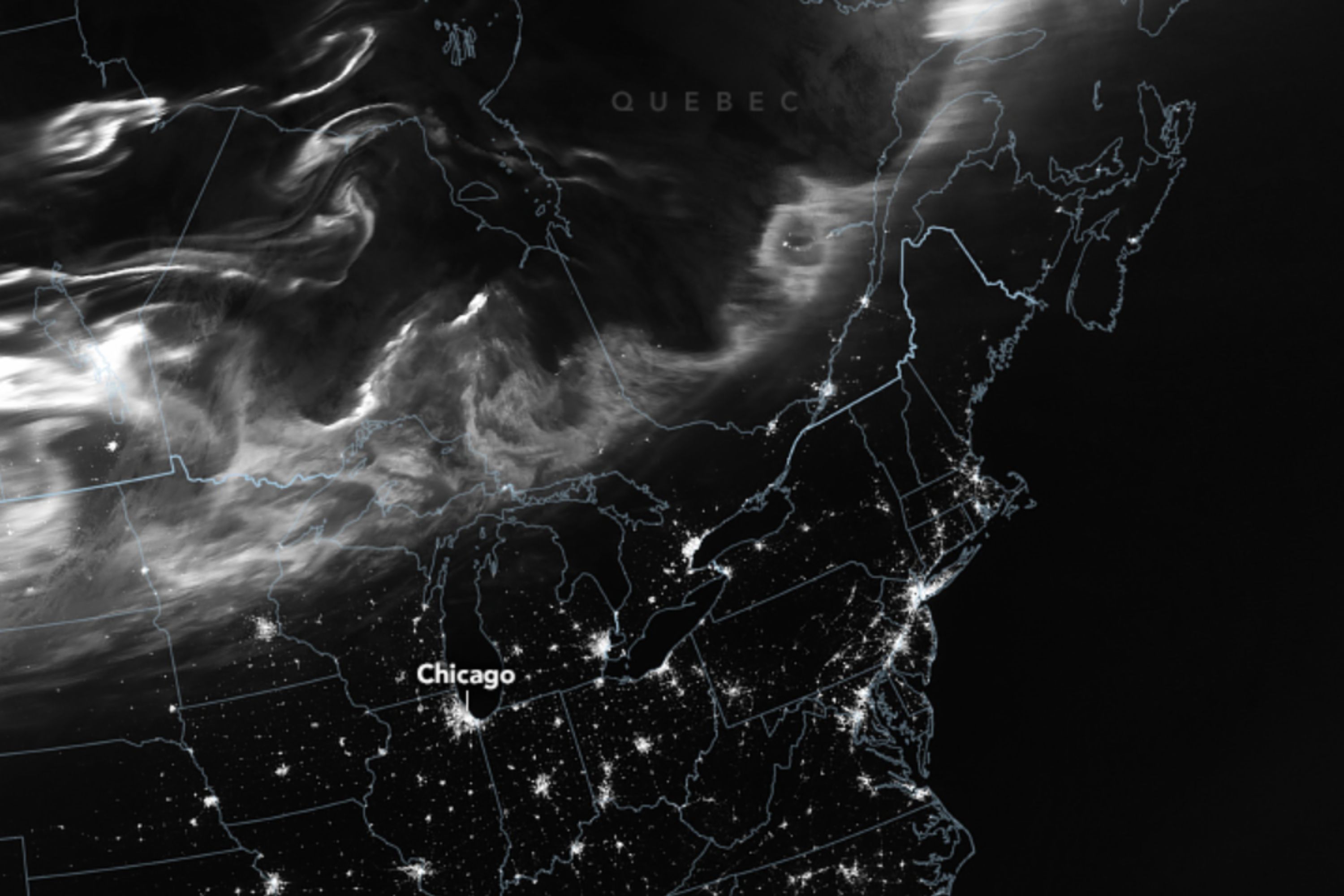

The NOAA-20 satellite’s VIIRS (Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite) took breathtaking images of the auroras dancing across the northern U.S. Astronauts aboard the International Space Station also shared their views of the vibrant light show.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Michala Garrison, using VIIRS day-night band data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE, GIBS/Worldview, and the Joint Polar Satellite System JPSS.

The interaction between the solar plasma and Earth’s magnetosphere causes magnetic reconnection, which disrupts the magnetic field. This disturbance redirects charged particles into Earth’s atmosphere, particularly in polar regions. When these high-energy particles collide with oxygen and nitrogen atoms, they illuminate the sky in shades of green and red.

Geomagnetic storms are rated from G1 (minor) to G5 (extreme). Not surprisingly, the more intense the storm, the further south you can see the northern lights. A recent G5 storm in May marked the first of its kind since 2003.

“Expected impacts increase with the rarity and severity of such events,” experts note. However, both the G5 storm in May and the Carrington Event in 1859, the strongest storm recorded, are classified at G5, despite their differences.

The sun goes burp and the atmosphere turns red. Spectacular not only from Earth but from orbit as well. This event caught both @dominickmatthew and I off guard. Aurora had been just so-so; we were out of energy at the end of a long day and reluctant to once again set up our… pic.twitter.com/gL6rjUiHJQ

— Don Pettit (@astro_Pettit) October 11, 2024

The Carrington Event disrupted 19th-century communication, causing telegraph systems to malfunction and sparking fires at some stations. Today’s powerful geomagnetic storms can threaten our infrastructure, leading to GPS disruptions and potential power outages.

“Geomagnetically Induced Currents (GICs) can overload power grids, which was a factor in the infamous Quebec blackouts of 1989. Fortunately, advancements in research have improved grid resilience,” experts say.

The aurora borealis dazzled many across North America last week due to the arrival of a severe geomagnetic storm.

JPSS satellites each witnessed a different experience as the northern lights fluctuated in intensity throughout the night. pic.twitter.com/CQGt3J1A2x

— CIRA (@CIRA_CSU) October 15, 2024

As the sun has officially entered a solar maximum phase, experts predict more intense geomagnetic storms similar to last week’s G4 and May’s G5 on the horizon. “We’re about two years into this maximum period, so expect another year of activity before it tapers down,” said Lisa Upton, co-chair of the Solar Cycle Prediction Panel during a recent NASA announcement on October 15.